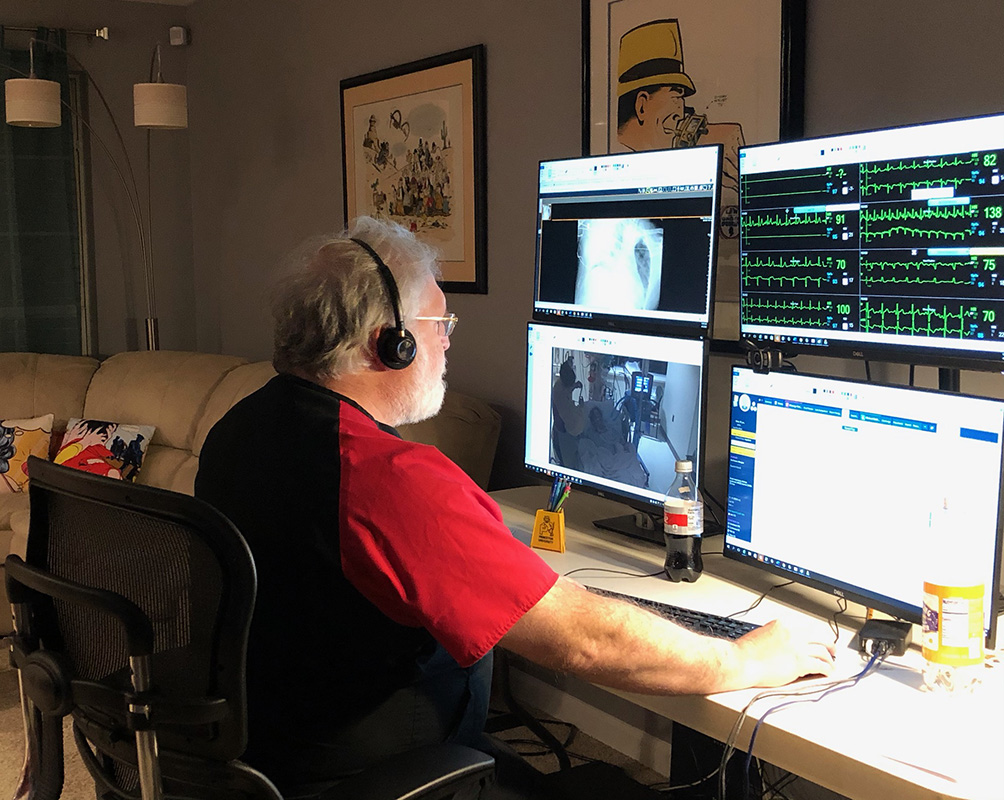

Steven Brown ’77 has practiced medicine in rural areas for more than 10 years, not by meeting patients in an office or by their hospital beds, but virtually, monitoring them in hospitals from Missouri and Arkansas to Oklahoma and Wisconsin. Now with COVID-19 he has turned his living room into a command center for 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. shifts.

The pulmonologist, based in St. Louis, Missouri, has four computer monitors with a dedicated router and server plus a highly sophisticated video camera that allow him to keep tabs on around 100 patients nightly. He estimates 15 to 20 percent of his patients may be new each time, many with COVID-19.

Although the native New Yorker says he was anguished not to return to his hometown when the pandemic hit there hard, he decided he could best serve helping rural ICU units connected to the Mercy Virtual Care Center. His employer allowed him to move operations to his home rather than continue at its physical hub, where its large medical team allows doctors to “see” patients where they are.

Brown, an early adopter to telemedicine, estimates he’s put in some 20,000 hours in the field. Many rural hospitals may have only two ICU beds but no ICU doctor, he says, “so I assist and keep the critical care local.”

“I can’t palpate an abdomen or hug someone who’s dying,” he adds, “but like Yogi Berra said, ‘You can observe a lot by watching.’” He admits that at times juggling his assignments can feel like a cross between “being an air traffic controller and playing whack-a-mole at Chucky Cheese” as he deals with patients’ immediate needs.

He typically starts his shift consulting with the day doctor to get a hand-off on the patients he will be watching. Then he monitors each, dialing oxygen up or down as needed, or ordering an x-ray or medications. He relies on the doctors and nurses onsite as “boots on the ground,” calling them for evaluations as his hands, ears, and eyes, but “I set the dials on how the air is delivered,” he says, “and monitor to see how that’s doing.”

Another big part of what Brown does is offer emotional support to colleagues. He’s often working with nurses who are in their 20s, and knows they are scared. He’s been in their place.

In the 1980s, Brown trained at Bellevue Hospital in New York City during the AIDS crisis. “My job was inserting IVs and doing lung biopsies. Every day I had a sense of fear for my own life and fear for the entire world.”

That experience, and handling subsequent medical crises like Legionnaires disease, propel him to do his best to keep colleagues’ spirits up, “doing as best I can without being able to hug.”