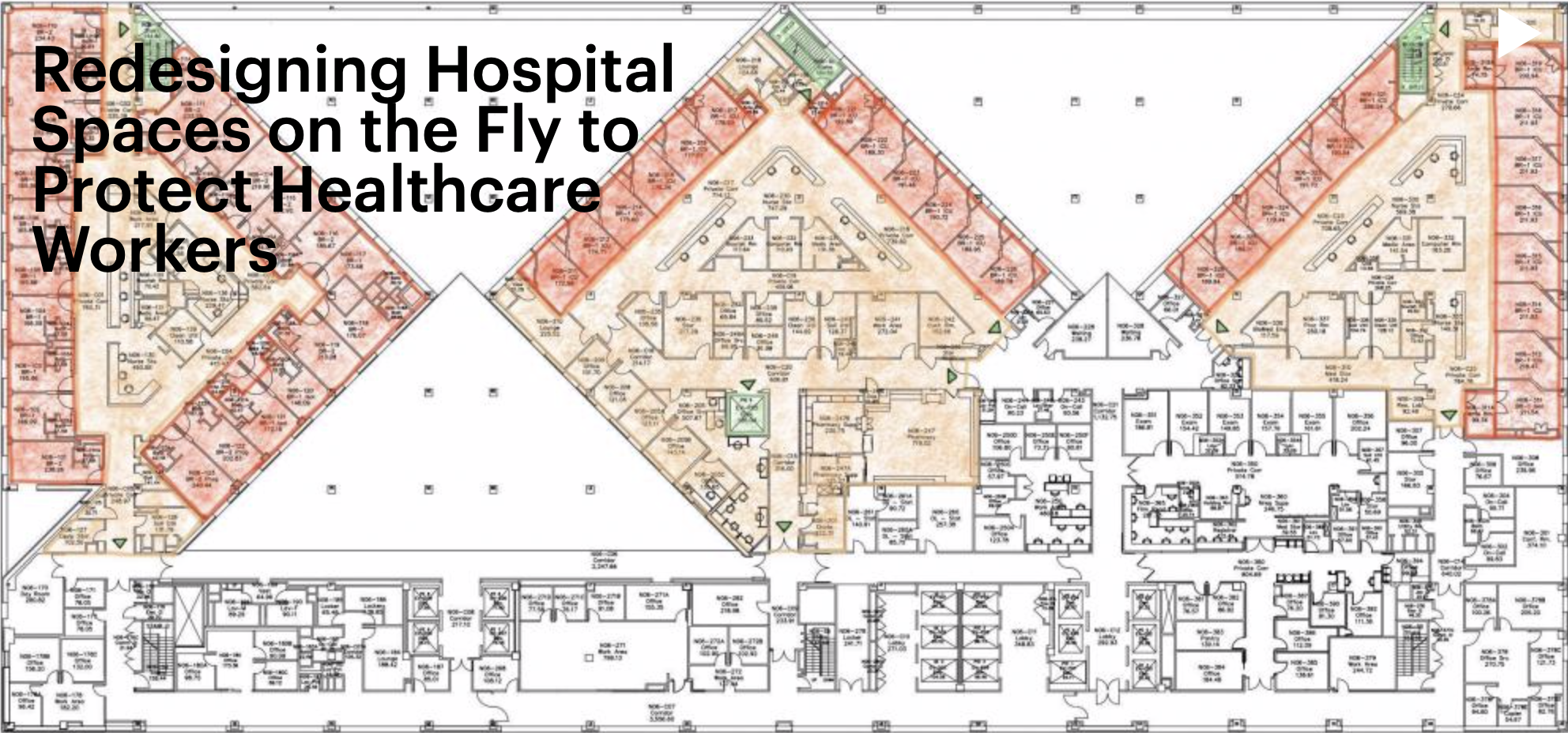

Hospitals hit hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic have been forced to convert and expand spaces in order to treat an unprecedented number of highly contagious patients. This would be a major adjustment during the best of circumstances, but repurposing infrastructure is even more challenging in the midst of an outbreak. Fortunately, MASS Design Group, a nonprofit architecture firm based in Boston and Kigali, Rwanda, partnered with the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City to research protocols so that hospitals can responsibly redesign existing spaces to provide the best care, while protecting their health care workers and mitigating the spread of infection as much as possible.

Jeff Mansfield ’08, Amie Shao ’06 *10 and Regina (Yang) Chen ’08 are members of the MASS team that spent three weeks in April studying the design layout and infection control protocols of the inpatient care units at Mount Sinai.

“These spaces weren’t really designed for this level of pandemic surge, and when you adapt spaces that are very different, you end up with a lack of consistency and a lack of clarity,” said Shao, who is based in Rwanda and had previously worked with healthcare facilities during outbreaks of cholera and tuberculosis. “A major concept that came up was this notion of what we are calling spatial literacy, the ability to read and understand spaces with the help of simple visual aids and design nudges.”

When a healthcare facility becomes stressed by a wave of COVID-19 patients, medical personnel often are required to work in different units or perform different functions with different colleagues. This unfamiliarity can make infection control protocols more difficult to follow.

Unable to visit Mount Sinai themselves, the MASS team arranged video tours with on-site clinicians to map the hospital’s spaces and interviewed personnel to determine what places were perceived as high-risk “red zones” for the spread of infection. They documented hospital activity with the use of time-lapse photography to identify high-traffic areas and better recognize potential vulnerabilities.

“Spatial literacy was a new idea at Mount Sinai,” Chen said. “There were a lot of conversations about ‘staff, stuff and systems,’ but very few about the ‘space’ and how it all works together to keep our patients, our doctors and our communities safe.”

The finished report, “The Role of Architecture in Fighting COVID-19: Redesigning Hospital Spaces on the Fly to Protect Healthcare Workers,” provided numerous recommendations, including extending the same strict infection control protocols for inpatient rooms to hallways and key thresholds, like entries into units. Design cues such as signage, markers and strategically located hand sanitizers are intended to alert staff and reinforce patterns of vigilance within the “red zones.” MASS, Mount Sinai Hospital and research partner Ariadne Labs hope to take their findings from this project to influence other hospitals preparing for surge conditions.

“The work that we did at Mount Sinai was about the staff and the health workers in those environments, because there really needs to be special attention to protect them in order to keep the whole system afloat,” Shao said.

The same spatial-strategies approach guided MASS’s other COVID-19 studies on restaurants and prison systems, the latter of which have been described as “petri dishes” for infection.

“Prisons are not designed to minimize infection controls,” Mansfield said. “Social distancing does not mean isolation, and outbreaks impact everyone: those who are incarcerated, the staff — the guards and wardens — and the communities impacted by mass incarceration. We really want to make sure that any changes we recommend are sustainable; but this is a moment where we’re experimenting with everything in the prisons, hospitals and school systems.”

Their team’s professional expertise is concentrated on assisting vulnerable populations, but it’s tempting to ask them to extrapolate their research and apply it to the typical open-office workplace layout that millions of Americans expect to return to once the pandemic subsides.

Shao imagined revamped open-offices that are more “semi-open,” perhaps with smaller work “neighborhoods” that are more spread out from each other.

Mansfield agreed. “There’s still going to be that human desire to want to connect, so I think that will lend itself to the need and the demand for a continued open floor plan. But I do agree that what an open floor plan looks like in the future as a result of the pandemic is different from what we have today.”

“Every single one of our spaces is going to be reconsidered in light of a ‘new normal,’” Chen added.